The House Magazine – 15th January 2001

The House Magazine – 15th January 2001

At the end of The Thirty-Nine Steps – the novel not the films – when all the villains have been caught, Buchan's central character says that he probably did his best work before he joined the Army. Sometimes I feel the same, having waged political campaigns for many years before entering Parliament.

I used to feel too academic to be a politician, but too political to be an academic. At too early an age I read with incredulity and frustration about the naïve pacifism and moral cowardice of the 1930s, which led to an unnecessary second world war. I really came into politics to try to prevent the same mistakes from being made again.

My family came to Britain from eastern Poland at the turn of the century. Most who remained were murdered by the Nazis, but a handful were saved at huge personal risk by a Polish farmer who hid them in a bunker under a barn for nearly two years.

All this means that I'm not a Utopian who thinks he knows how others should lead their lives. What I understand is the mentality of those who would enslave them. My role in politics is to stop horrible things from happening – not to promote a vision of an earthly paradise.

When I started thinking politically in my teens, I saw the dangers of disarming in the face of a similar threat; but it was now from the totalitarian left instead of the totalitarian right. In the 1980s, I campaigned to keep Britain's nuclear deterrent and ensure the vital deployment of NATO cruise missiles. These days, almost everyone admits that that was correct, but it was a very different story then.

Other campaigns included the adoption of postal ballots to end trade union election ballot-rigging, and the introduction of legal protection for schoolchildren against political indoctrination in the classroom. The most controversial one, though, was in Newham North-East, where militant entryists had deselected a Labour cabinet minister. A friend and I decided that, if Labour would do nothing about it, we would. So I, too, entered the local Labour Party for about 18 months to give them a taste of their own medicine – on the grounds that if other people break the big rules, I won't be bound by lesser conventions. It is like peaceful democracies in wartime: they have to retaliate with measures which they wouldn't dream of initiating.

I grew up in Swansea and went to the same state grammar school as my father, Sam. The difference was that he had to leave at 14 to help his father as a tailor. He used to tell me that he would be the last of the tailors in my family. He is an exceptionally intelligent man who would undoubtedly have succeeded at university if he had been able to complete his education in the late 1920s. The university grant system gave me my opportunity, and I never approved of the changeover to top-up loans – let alone for tuition fees.

I grew up in Swansea and went to the same state grammar school as my father, Sam. The difference was that he had to leave at 14 to help his father as a tailor. He used to tell me that he would be the last of the tailors in my family. He is an exceptionally intelligent man who would undoubtedly have succeeded at university if he had been able to complete his education in the late 1920s. The university grant system gave me my opportunity, and I never approved of the changeover to top-up loans – let alone for tuition fees.

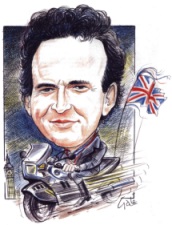

My motorcycle has become a bit of a trademark. I had a Honda 50 at college, graduating to a CB 175 during the Newham campaign. When that finished I had to keep myself alive for six months before resuming my doctoral work – in strategic studies, naturally! So I became a dispatch rider in London, with two other bikers and a controller. We were a little commune, actually, splitting the proceeds equally amongst the four of us.

When I went to Conservative Central Office as Deputy Research Director in 1990, I acquired my present BMW 750. Some see this as ironic in view of my Eurosceptic credentials, but I've always believed the best way to keep Germany healthily democratic is to keep her prosperous. (I also like the idea of Hitler roasting down below, as I ride around on a BMW pursuing my political objectives!)

My brief at CCO could loosely be described as "negative" campaigning: in other words, showing not why we were good and should be elected but why the other lot were no good and should be rejected. Over a six-year period there, I became increasingly alarmed at the direction of the post-Thatcher Conservative government. This finally persuaded me seriously to seek a seat.

The failure to allow the moderate Bosnian Moslems the means of defending their families particularly appalled me. The excuse was that "We shouldn't help create a level killing-field". What is the alternative, unless it is a killing-field where the aggressors can murder the defenceless? (That is why, in March 1998, I called for military action against Milosevic, a year before it happened, and why I supported the Government throughout the Kosovo campaign. For similar reasons, I strongly back war crimes trials and the proposed International Criminal Court.) The final straw was the unprincipled "wait and see" policy on the single European currency – a policy ingloriously common to Government and Opposition alike in the run-up to the 1997 election.

With my views, I knew that the only way of winning a worthwhile nomination would be to find a seat where people would want me because they really knew me and approved of me. Two splendid women, Pamela Combes and Wendy Burchall (later my Agent) introduced me to the wonders of the two New Forest constituencies early in 1995. For ten months I spent every spare moment there and in February 1996 was selected for New Forest East.

It was very important to me, if I was to devote the rest of my working life to a constituency, that I should enjoy it. As I've never been a polymath – my parliamentary work overwhelmingly concerns defence, foreign affairs, freedom and security – the likelihood of my holding a ministerial post in peacetime is small. Therefore, being a good constituency MP must be a pleasure, not just a chore to be endured on the route to the front bench.

Though it does have drawbacks, the internet has enabled me to assemble a comprehensive collection of what I've said, done and written politically both in and outside Parliament. No doubt, I am the most frequent visitor to the website (www.julianlewis.net)! It serves as a handy electronic archive as well as a practical way of accounting to my electors ...

[For a Biographical Note on Julian's career, click here.]